1. Introduction

This contribution discusses the challenges, solutions and open questions connected to the reusability and therefore persistence of web-based research from the perspective of the AlpiLinK project (Rabanus et al. 2023 ff.) and its predecessor, VinKo.

VinKo and AlpiLinK are both linguistic projects focusing on non-standard and minority languages, many of which are classified as 'definitely endangered' or 'vulnerable' by UNESCO (Moseley 2010, Map 8). As such, the preservation and maintained accessibility of its data is of major concern, not only for the academic community, but even more so for local community stakeholders. During the VinKo project it became evident that much valuable data was collected aside from the grammatical features that were the focus of the research team. Despite the many new technical opportunities for connecting people and information of the last decades, the mainstream output of scientific research has not evolved majorly beyond e-journals with procedures and standards almost identical to their paper-based predecessors (the Korpus im Text this article is pubished in is a rare exception). Despite having many new options available for sharing not only results, but also the underlying data, community-wide standards for the long-term storage and accessibility of online data and information for the general public are still actively being developed. The reasons for this are multifold; partly financial when it comes to the publishing practices of major journals, but also practically; digital media are fragile and quickly become obsolete. In the last few years, the discussion on data management has taken flight, resulting in increasingly widely used FAIR (findable, accessible, interoperable, reusable) data standards for scientific data. The FAIR data concept forms an integral part of the Open Science movement and addresses many of the issues that linguists collaborating with minority and/or disenfranchised speech communities have always faced.

In transitioning from the VinKo to the AlpiLinK project, maintaining access to the VinKo data, information and digital infrastructure for all interested parties involved was a priority. Especially the digital infrastructure proved to be a much bigger challenge than originally anticipated. The following section discusses both projects and their data, online systems, stakeholders and data management plans. Section 3 discusses the process of the transition itself and what parts of the original VinKo project were maintained and which parts were lost. The final section is a discussion of the problems faced during the transition and what this entails for the larger landscape of digital research and the persistence of its results.

2. Projects

2.1. The VinKo system

The VinKo project (Varieties in Contact 2017-2023) was a collaboration of the University of Verona with the University of Trento and the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano. Its research focus was the documentation and description of the dialects and minority languages spoken in northeastern Italy (specifically Trentino-South Tyrol and Veneto). During its 6-year run, the project collected almost 190,000 audio files from 1439 participants. The audio files range from single words to full sentences. All data collected in the project is freely available in the VinKo Corpus (Rabanus et al. 2023a). A summary of the obtained results is listed below in Table 1 and the coverage of the geographical area can be found on Map 1. Each hexagon indicates a municipality for which there is at least one participant present in the corpus.

| Number of speakers | 1439 |

| Number of locations | 387 |

| Number of audio files | 189.679 |

| Language varieties | 12 |

VinKo data (Corpus 1.2)

Locations with VinKo data; the shades of blue indicate Romance varieties (light=Veneto dialects, bright=Ladin, dark=Trentino dialects), the shades of yellow Germanic varieties (light=Tyrolean, dark=language islands, e.g. Cimbrian, Mòcheno, Sauris, Sappada).

This section focuses exclusively on the online systems, data collection and stakeholders of the VinKo project, for a more detailed description of the VinKo corpus, please see Kruijt/Rabanus/Tagliani 2023.

2.1.1. Online system: data collection and representation

The data collection for VinKo was done via online crowdsourcing. On the website, participants completed an online linguistic questionnaire by recording spoken responses to (image-aided) translation tasks, a word pronunciation task and a question-answer task. During the registration phase, participants were presented with the data processing agreement of the project. It detailed the current and future usages of the supplied data, pointed out any potential risks to participants (e.g. identification on basis of voice), and informed them of their rights regarding data retraction and deletion under the GDPR-guidelines. The data was licensed as Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Italy (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IT). The topics of interest were phenomena of language contact and contact-induced language change in the areas of phonology, morphology and syntax. Some items of the questionnaire were presented to speakers from all language varieties, while other items were language specific. For example, the translation task presented to Cimbrian speakers or Venetan speakers had partial overlap, but also included stimuli exclusively for the language variety in question. The analysis of the data has yielded publications on the morphology of articles and pronouns (Kruijt 2022), subject expletives in weather verbs (Tomaselli/Bidese 2023), and expletive articles with personal names (Rabanus 2023).

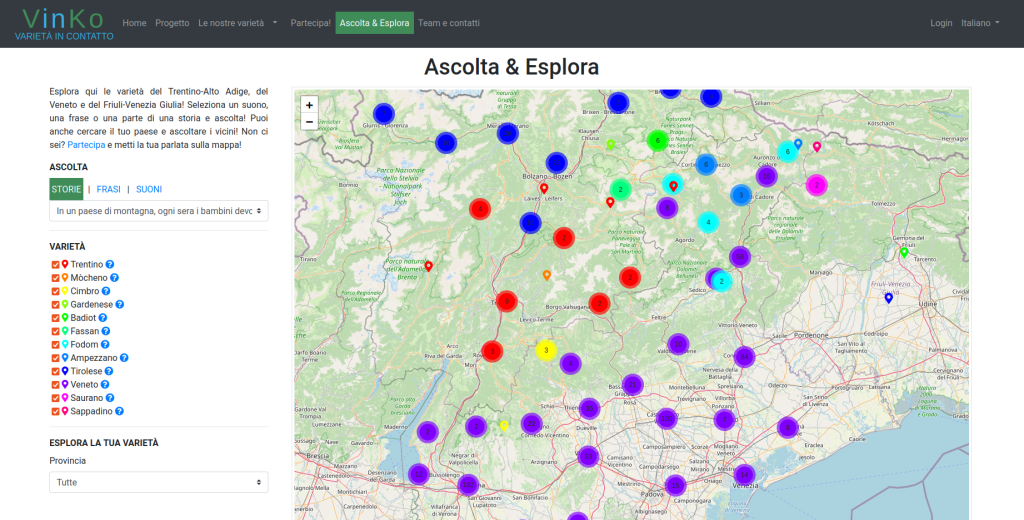

The VinKo website (taken offline in June 2023) formed the primary access point to the data. It served as the main method of reaching and informing the general audience, it was the gateway to the linguistic questionnaire and, via a password-protected section (with free registration for researchers), allowed access to all of the collected data. The public spaces of the website were primarily used by the general public and its writing style was aimed at a general audience without knowledge of linguistic terminology or concepts. The pages with static information regarding the linguistic varieties of the area were reported as interesting and informative by participants. However, the most positive feedback was received about the interactive map, a section of the website we called "Listen & Explore", see Figure 1. It featured a map of the research area. By selecting a stimulus sentence from the questionnaire, you could listen to the audio recordings of that specific sentence across different language families or dialect varieties. The idea behind the map was that the effect of participation in the crowdsourcing was tangible and therefore more rewarding for participants. It also made it very easy to engage with the data and explore the notions of linguistic diversity and local linguistic heritage in an accessible way.

Screenshot of VinKo's "Listen & Explore" section (Italian-language version)

The technical development of the website was done by the University of Trento and during the run of the project was taken over by the technical staff of the University of Verona. For the entire project time, the system remained hosted on the servers of the University of Trento. The system was designed using exclusively open non-proprietary software packages (e.g. Leaflet for the map) and it was made entirely in-house. Any changes to the content needed direct intervention of the technical staff and took a long time to implement.

2.1.2. Stakeholders

The most obvious stakeholders in the project were the researchers and universities aligned with the project and other linguists working on the non-standard language varieties of Veneto and Trentino-South Tyrol. The crowdsourcing aspect of the project and the language endangerment status of the linguistic varieties involved, added an important public outreach aspect, not only in the data collection but also in the presentation of the results. Additionally, during VinKo a Citizen Science subproject was initiated called VinKiamo. VinKiamo created a fruitful collaboration with high schools in the Veneto region by involving the students and their teachers with the data collection (see the VinKiamo project based in Veneto here: https://sites.hss.univr.it/vinkiamo/). Participation in the data collection trained the students in their digital, linguistic and active citizenship skills. During the teaching hours provided by the University of Verona, the interactive map was used to illustrate linguistic differences and similarities between Romance and Germanic varieties. It also situated dialects and minority languages firmly in the modern world and as prestigious objects worthy of study. As such, the data is being employed not only in scientific cycles, but also for educational purposes outside the university, for more details on the Citizen-Science aspect please see Bertollo/Rabanus 2023.

2.1.3. Data management: preservation and archivation

VinKo did not have a data management plan (henceforth DMP) present at the start of the project. Instead, the DMP for the project was formulated and implemented only after a large portion of the data had already been collected. The late creation of the DMP immediately brought to light some issues regarding data management and long-term preservation that had not been considered at the start of VinKo. The short-term data storage was taken care from the start of the project by the Progetto di eccellenza: Le Digital Humanities applicate alle lingue e letterature straniere (2018-2022), a special funding for the research in digital humanities at the Department of Foreign Langauges and Literatures of the University of Verona. This funding provided a 5-year guarantee for data and software storage on the University server. After this period, there was no guarantee that the data or the software would be maintained on the server. As such, the DMP was designed with the purpose to ensure access to the data after this period. Due to it being introduced in such a late stage of the project, the format of the data as well as the structure had to be completely overhauled in order for it to be suitable for archiving and potential future reuse. In the end it took a lot of additional time and energy, almost 2 years, to accomplish. This expense was unforeseen in the original funding proposal and as such had to be financed with external funds.

The VinKo data were archived at the Eurac Research CLARIN Centre (henceforth ERCC), based in Bozen-Bolzano in South-Tyrol, under the name of VinKo (Varieties in Contact) Corpus (Rabanus et al. 2023a). As alluded to in the name, this centre is associated with the CLARIN (Common Language Resources and Technology Infrastructure) infrastructure of the European Union meaning in practical terms that it adheres to well-defined standards for digital infrastructure including standard schemes for metadata. As a local and language-specialized repository, it situates the data in the research area and increases the findability by being hosted together with similar datasets.

The linguistic data collected in the project was in this way safeguarded, but the online systems and webpages were not considered in the DMP and therefore were left mostly adrift after VinKo ended. Originally the idea had been that AlpiLinK would adopt the existing online system and further develop it, but this proved to be unworkable, as will be further explained in section 2.2.1.

2.2. The AlpiLinK system

AlpiLinK (Alpine Languages in Contact, <https://alpilink.it>, a 'project of relevant national interest' [PRIN] financed by the Italian Research Ministry) is a joined project of the Universities of Verona, Trento, Turin, Valle D'Aosta and the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano. AlpiLinK is built around three keywords: documentation, explanation and participation. These relate to the project aims of scientific documentation of the Germanic, Romance and Slavic non-standard and minority languages spoken in alpine Italy via community participation in the collection of spoken-language data. The collected data is analyzed to investigate language contact and to provide an explanation of the found phenomena for both academic and laymen audiences. The data collection of AlpiLinK is currently ongoing and at the moment of writing has collected over 39,000 audio files. Per speaker on average 42 recordings are available (primarily recordings of single sentences). Table 2 provides an overview of the results of the data collection so far. Map 2 below indicates all locations for which data is present.

| Number of informants | 1174 |

| Number of locations | 593 |

| Number of audio files | 39.019 |

| Language varieties | 15 |

AlpiLinK data (as of August 2024)

Locations with AlpiLinK data (as of August 2024), colors indicate language variety: the shades of blue indicate Romance varieties (from lighest to darkest: Friulian, Venetan, Lombard, Piemontese, Francoprovençal, Occitan, Ladin, Trentino), the shades of yellow Germanic varieties (light=Tyrolean, dark=language islands, e.g. Cimbrian, Mòcheno, Sauris, Sappada, Walser), and green Slavic varieties (e.g. Resia).

2.2.1. Online systems: data collection and representation

The general idea behind the data collection of AlpiLinK is very similar to VinKo. It is done via online crowdsourcing and through the lessons learned in VinKo, the crowdsourcing is now facilitated by increased and frequent public communication and school projects under the label VinKiamo across most regions involved in the project. It uses an online linguistic questionnaire in which participants are asked to make audio recordings of their responses to a variety of tasks (in combination with a few multiple choice questions regarding name truncation). The tasks include translation, tense and word class transformation, and image description. The topics of interest are phenomena of language contact and contact-induced language change in the areas of phonology, morphology and syntax, e.g. pronominal clitics, article use with proper nouns, negation, possession, and selected features in word formation, phonology and syntax. Additionally to the brief sociolinguistic information it collects from participants at the start, it also has a final free section in which participants are asked to volunteer more information about their linguistic profile, e.g. what language they spoke growing up, what was spoken in the local neighborhood. This can be done in any language of their choosing. These recordings will not get identical data for all locations, as participants themselves decided what information they think is relevant and what they want to share. It does provide an unique insight into their lived linguistic experience and linguistic situation on the ground, and are often quite revealing in language attitudes and prestige. Apart from linguistic data, AlpiLinK also has a section dedicated to the linguistic landscape of the area. The data collection for this aspect is done separately from the linguistic questionnaire and is composed of a form through which people can contribute photos of language use in the public domain.

The AlpiLinK website is primarily aimed at the general public and serves to inform, interest and engage. For each language variety in the research area, there is a dedicated section with general information and some audio data if available. They also include links to online linguistic resources and local cultural and/or linguistic associations. A new interactive map has been developed for AlpiLinK. It has much of the same functionalities as the VinKo map, but the general look of the map and crucially the back-end system have been improved upon. It is an open system which can easily be adapted to include outside data. A selection of the VinKo data has been migrated to the new map and is shown alongside the newly collected AlpiLinK data.

AlpiLinK was originally planned to keep the same digital infrastructure as VinKo, necessitating only changes in the content. However, the digital infrastructure being fractured across two departments of two different universities soon proved to be problematic in its application. Also, the in-house design of the VinKo system was difficult and costly to maintain and keep up-to-date. As it did not fit with any of the technical applications of other projects of the University of Verona, the necessary allotment of time on the technician's part was much larger than could be justified. As such, the AlpiLinK online structure was approached quite differently from VinKo. In order to make the upkeep and creation of the project technical infrastructure more time- and cost-effective, the online system is composed of commercial proprietary softwares rather than softwares build in-house. The AlpiLinK website is hosted via WordPress and the lay-out is a project-dedicated WordPress theme. WordPress allows for easy modification of the content for all permitted users. As the platform account is shared across the University of Verona and maintenance is run by the technical staff, the costs of acquirement and upkeep are low and the necessary updates and security protocols are guaranteed for the foreseeable future. The data collection is done via an external company, called Phonic, which specializes in online surveys with the option to collected speech data in addition to written data. Phonic works with a subscription model, and so the service can be bought in tailored for the runtime and expected traffic of the project. Unfortunately at the time of writing, the company has indicated that they will stop running the Phonic software in the following year. For the timeline of AlpiLinK, this does not majorly inconvenience the project, but it does highlight the vulnerabilities of working with external for-profit companies. The two maps on the AlpiLinK website, one with the oral linguistic data and one with the linguistic landscape data, has also both been sourced out-of-house. The linguistic landscape map derives from the work of the Lingscape project of the University of Luxembourg (Purschke/Gilles 2016 ff.) and the data is placed on their servers. The linguistic data map has been built by Chambra D'Oc, a non-profit organization specialized in the tutelage and protection of minority language, with a focus on Occitan and Francoprovençal. Their staff and people involved in the creation of the map have previously done work on dictionaries for communities in the area of interest, and through shared interest and stake this could lead to interesting tie-ins with the AlpiLinK data in the future.

2.2.2. Stakeholders

The stakeholders in AlpiLinK are very similar to those of VinKo. In the academic community, the project systems and data are of interest to the researchers and universities associated with the project as well as other linguists working on the non-standard varieties and minority languages spoken in the alpine region and/or those interested in language contact. As with VinKo, local communities and the participants of the crowdsourced questionnaire are vital partners in the project. The VinKiamo subproject working with local high schools has been continued during AlpiLink and expanded into more regions. The way that the VinKiamo activity is approached is region specific, as there may be administrative and practical changes that need to be made to make the concept achievable. The training provided during the VinKiamo activity has also extended to include teacher training and the provision of teaching materials. This has further cemented the importance of the data for uses outside of academia.

2.2.3. Data management: preservation and archiving

Unlike VinKo, AlpiLinK did create a DMP from the start of the project and as such it has set out clear data standards and data management processes from the first moment that data was collected. The raw data that is downloaded directly from the linguistic questionnaire software does still need to be cleaned up, but this is done on a monthly or bimonthly basis as the data comes in. Once cleaned-up and processed, the data is stored in an interoperable format (FLAC and CSV), structured cohesively with a clear file labelling system and straight-away archived at the chosen repository. The data is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). The latest version of the AlpiLinK Corpus (at the time of writing v1.1.4, Rabanus et al. 2024) can be found using the following DOI:10.5281/zenodo.8360169. The data is stored in a different location from VinKo, as the ERCC was not the best suited repository for frequent versioning. Instead, the Zenodo repository was chosen. This repository is a general scientific repository hosted by CERN (European Organization for Nuclear Research), which has become a hub for EU research data, and it ensures the preservation of the data at least for the next 20 years. The drawbacks of this choice are that they have no expertise in digital items pertaining to linguistics specifically, nor does it situate the dataset in the vicinity of similar datasets. This could limit the findability of the dataset or cause problems in the used formats in the long run. However, in the future, the corpus could always be migrated to another repository if so desired. The DMP was vital in ensuring that the data are being archived during the project, limiting the risk of loss and maximizing the use and access of the data, to both the research team and external academics. It also means that the resources needed to ensure the preservation of the dataset were included in the original funding proposal and are as such ensured.

The online system and the linguistic map are not covered by the DMP and face the same risks as the VinKo versions faced when the project finished. The proprietary software programs used in the creation of the online system cannot be exported or archived, though both WordPress and Phonic allow for export of the content. The linguistic map remains for the moment an open question, depending on the inclination and options of the developers for how long they can ensure the maintenance for and the software used in the creation.

3. The VinKo-to-AlpiLinK transition

This section briefly discusses what parts of VinKo have persisted after the closure of the project and what parts have been lost. It also briefly touches on the resources that were needed to accomplish this and how the different stakeholders in the project were affected by the decisions made before and during the transition.

3.1. What remained accessible

During the transition from VinKo to AlpiLinK, while it was projected to retain as much of the digital infrastructure as possible, the main focus was on safeguarding the data. From the beginning it was clear that at least a part of the investigated features of VinKo would be adopted by AlpiLinK, and so for the research aims it was integral that the data remained available. As such much of the available resources in the time between projects was aimed at safeguarding and structuring the data. This resulted in the VinKo (Varieties in Contact) Corpus (ultimate version 1.2, Rabanus et al. 2023a) stored at the ERCC in Bozen-Bolzano. The ERCC in their Preservation Policy (the policy can be found here on their website) states that they are committed to long-term preservation of the items deposited by adopting the current best practices in the digital preservation. They are also committed to making "every effort" to account for any changes in what constitutes best standards, for example by migrating items to another format if the preferred formats change over time. Furthermore, contributions are not "locked in" and can be moved to another repository without problems. All in all that means that we can be quite certain that the persistence of the VinKo dataset for the foreseeable future is guaranteed and all possible provisions have been made for its long term future. It must be recognized that digital repositories and datasets remain more vulnerable to the passage of time than physical copies of items. Even so, the CLARIN infrastructure offers institutional certainties that would be very difficult to obtain elsewhere. The issues regarding data security and management are faced by practically all scholars in the modern world and sustained institutional action on these fronts can be reasonably expected.

For the academic stakeholders of the project this means that the elements most crucial to them have been not only preserved, but also remain freely accessible. If we look again at the FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) acronym, the VinKo Corpus ticks many boxes. The ERCC metadata of the project is standardized to be easily findable by crawlers and search enginges. Academic publications citing the dataset should also make the corpus more findable as a resource for scientific research. The corpus itself is composed of primarily two formats: FLAC for the audio files and CSV for the metadata files. This makes it a rather unsophisticated dataset (no possibilities for making a query as, for example, one could in a SQLite database), which comes with the advantage of having the dataset be easily accessed and reused by the less-technically gifted researchers among us. It is also widely interoperable as these formats can be imported in most software programs a linguist would use (with the notable exception of ELAN, an open source software for the annotation of audio and video recordings, which cannot import FLAC). That the corpus is suitable for reuse and that it can be integrated in new online tools without problems has already been made evident by the creation of the new map for AlpiLinK. The new map combines data from both AlpiLinK and VinKo, and the incorporation of the data from the VinKo corpus required only minimal work on the dataset itself due to its software- and reuse neutral stance.

3.2. What parts perished

Apart from the dataset itself, though admittedly a crucial part of the project, little else has survived the transition. Since it was first planned to adopt the software into the new AlpiLinK project, no further provisions were made for its preservation. The vulnerabilities of digital infrastructure however very quickly became apparent. Up until then, the system had been hosted on the servers of the University of Trento, where it had been originally developed. Even after the maintenance had been taken over by the technical staff at the University of Verona, Trento remained the host, as this was the easiest solution at the time. However, from June 2023 on, technical and organizational problems emerged. The VinKo system was hosted on a server with PHP version 7.2 for which no security updates were available anymore. The technical staff of the University of Trento upgraded PHP from version 7.2 to version 8.2, without changing the PHP scripts of the VInKo program code. The result was the inaccessibility of the VinKo services, first of all of the interactive map. The modification of the program code, which had to be made by the technical staff of the University of Verona, took more than a month and demonstrated that the maintenance of the VinKo system, divided between two universities, was too complicated and made the system too vulnerable. It was agreed that only the interactive ap and the back-end data access were to be kept online temporarily, and the rest of the webpages would be automatically redirected to the AlpiLinK webpage. This solution was meant to bridge the gap between the end of the VinKo project and the creation of a new system that would cover all the functions of the old one. Once this grace period was up, also these parts of the system would be closed down - which happened at the beginning of 2025. From then on every request to <https://vinko.it> is automatically redirected to <https://alpilink.it/vinko> where a summary of the project and links to VinKo data and results are located. The ownership of the vinko.it domain was also transferred from the University of Trento, no longer willing to pay the domain for an external service, to the University of Verona to guarantee replies to vinko.it requests for the foreseeable future. However, the solution also implied that apart from the contents, also the hours of technical work that went into the development of the website and online map have been lost.

When it came to saving as much of the content of these pages as possible, this was a relatively simple job for the project description and linguistic profiles webpages. An easy copy-paste salvaged the information on them and much of what could be found on them has been incorporated in some way on the new AlpiLinK pages. No original copies of these pages have been saved, so direct quotations or references to them cannot be checked anymore. This was seen as a small trade-in with little consequences for the majority of users. Much more crucial to users of the online platform, and especially to the VinKiamo subproject, was the VinKo interactive map. The map played a big part in the classroom teaching and it was the only way for a general audience to directly interact with the data that they themselves had collected. From the feedback from the school project, it is clear that community stakeholders put more importance on lexicon than on grammatical features which, for example, you would find in the scientific output of VinKo. The map, however, does meet this need much better. Even though neither project targets lexical items specifically, they are nonetheless produced in the tasks. For example, VinKo sentence T0303 was targeted at the collection of personal pronouns, but also it elicited the lexical item for 'girl'. By selecting this stimulus on the map, the user could explore for themselves the different dialectal translations found in the dataset, ranging from Romance tosa/buteleta/fiola to the Germanic Gitsch/Maadl.

The online system itself therefore formed the most important part of the community stakeholders. As the suppliers of the data via the crowdsourcing aspect of the project, they have the right to access their own data and maintaining that access should be seen as an obligation to the research team. Even with the online system taken down, technically, community stakeholders have the same amount of access to the data as academic stakeholders, namely via the corpus. However, it must be recognized that the raw data is of little interest to most participants and in practical terms is neither very accessible nor findable to them. Outside of academic circles one would be unlikely to come across a scientific repository on your own or be exposed to a conference paper quoting the data. Also the relative thresholds for access and reuse are higher for community stakeholders. The main difficulty does not lie with paywalls or institutional memberships, as it is the case for some academic outputs, but with the time one would need to invest to meaningfully interact with the dataset. The loss of the online system impacts the community stakeholders more than it does the academic stakeholders, and in projects with a participatory and collaborative nature this should not be forgotten.

4. Discussion

What we learned from the VinKo to AlpiLinK transition is that preserving a dataset in isolation is relatively easy with the proper planning. However, preserving linguistic data embedded meaningfully in its online environment is much more challenging and something we have no clear strategy for yet. It also brought to the forefront some key questions to address in the proposal stages of a project. Questions like "what is absolutely necessary that remains accessible at the end of a project?", "what would be desirable to remain accessible?", and "which stakeholders get prioritized in choosing what parts of the project are preserved?". It should also be considered what the implications are for the allocation of project resources.

In the case of VinKo, the collected data was a crucial part of the persistence of the research, and it got allocated the majority of the available funds. This left little time and room for consideration of the online system and its future. The technical infrastructure was largely lost, meaning that the investments that were made on this front yielded only short-lived results. The community stakeholders, that had the most interest in the maintenance of the online system, in the end maintained consistent access to the data, because the AlpiLinK project features the same kind of interactive map in which all the VinKo data had been integrated which were previously available via the VinKo map. However, this was in no way guaranteed during the transition and more due to persistence on the part of the team and some luck than to a concrete strategy from the beginning.

From VinKo, we learned important lessons in data management and the experience has been incredibly helpful in the set-up of the AlpiLinK project. However, on the online research system part we are at a loss for concrete answers. We strongly feel that it would be beneficial to have available community-wide standards and best practices surrounding the preservation and maintenance of online resources and research outputs. We recognize that this would necessitate long-term funding on a level which is often difficult to obtain and technical assistance that transcends the runtime of the individual project. At the moment, getting institutional academic recognition for online scholarship in non-traditional formats, like the Korpus im Text initiative this article is published in, is difficult and fostering the needed level of expertise is practically impossible on a project-per-project basis. The lack of resources often leads to private companies being employed to supply the technical expertise. As a consequence, the (public) project funding flows to private companies rather than being used to strengthen the knowledge base of university institutions. A critical look at the current funding and academic reward systems is long overdue and individual projects should carefully consider the best allocation of their resources for acquiring the technical support they need not only during a project, but also crucially after its end.

Bibliography

- Bertollo/Rabanus 2023 = Bertollo, Sabrina / Rabanus, Stefan (2023): VinKiamo: ein Citizen-Science-Projekt für Schulen zur Förderung von (sprach-) übergreifenden Kompetenzen, in: Alsic, vol. 26, 1, 1-19 (Link).

- Kruijt 2022 = Kruijt, Anne (2022): Crowdsourcing language contact: pronoun and article morphology in Trentino-South Tyrol and Veneto, Verona, University of Verona.

- Kruijt/Rabanus/Tagliani 2023 = Kruijt, Anne / Rabanus, Stefan / Tagliani, Marta (2023): The VinKo-Corpus: Oral data from Romance and Germanic local varieties of Northern Italy, in: Kupietz, Marc / Schmidt, Thomas (Eds.), Neue Entwicklungen in der Korpuslandschaft der Germanistik: Beiträge zur IDS-Methodenmesse 2022. Korpuslinguistik und Interdisziplinäre Perspektiven auf Sprache - Corpus linguistics and Interdisciplinary perspectives on Language (CLIP), Narr Francke Attempto.

- Moseley 2010 = Moseley, Christopher (32010): Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger, Paris, UNESCO.

- Purschke/Gilles 2016 ff. = Purschke, Christoph / Gilles, Peter (2016 ff.): Lingscape – Citizen science meets linguistic landscaping., Esch-sur-Alzette, University of Luxembourg (Link).

- Rabanus 2023 = Rabanus, Stefan (2023): Nome di battesimo e articolo espletivo – crowdsourcing e cartografica linguistica nello studio della variazione linguistica in Trentino-Alto Adige e Veneto, in: Schöntag, Roger / Linzmeier, Laura (Eds.), Neue Ansätze und Perspektiven zur sprachlichen Raumkonzeption und Geolinguistik: Fallstudien aus der Romania und der Germania, Peter Lang.

- Rabanus et al. 2023 ff. = Rabanus, Stefan / Kruijt, Anne / Alber, Birgit / Bidese, Ermenegildo / Gaeta, Livio / Raimondi, Gianmario (2023): AlpiLinK. German-Romance language contact in the Italian Alps: documentation, explanation, participation. In collaboration with Paolo Benedetto Mas, Sabrina Bertollo, Jan Casalicchio, Raffaele Cioffi, Patrizia Cordin, Michele Cosentino, Silvia dal Negro, Alexander Glück, Joachim Kokkelmans, Andriano Murelli, Andrea Padovan, Aline Pons, Matteo Rivoira, Marta Tagliani, Caterina Saracco, Emily Siviero, Alessandra Tomaselli, Ruth Videsott, Alessandro Vietti & Barbara Vogt. (Link).

- Rabanus et al. 2023a = Rabanus, Stefan / Kruijt, Anne / Tagliani, Marta / Tomaselli, Alessandra / Padovan, Andrea / Alber, Birgit / Cordin, Patrizia / Zamparelli, Roberto / Vogt, Barbara Maria (2023): VinKo (Varieties in Contact) Corpus v1.2, Eurac Research CLARIN Centre [University of Verona] (Link).

- Rabanus et al. 2024 = Rabanus, Stefan / Kruijt, Anne / Alber, Birgit / Bidese, Ermenegildo / Gaeta, Livio / Raimondi, Gianmario (2024): AlpiLinK Corpus 1.1.4. In collaboration with Paolo Benedetto Mas, Sabrina Bertollo, Angelica Bonelli, Jan Casalicchio, Raffaele Cioffi, Patrizia Cordin, Silvia Dal Negro, Alexander Glück, Joachim Kokkelmans, Adriano Murelli, Andrea Padovan, Aline Pons, Matteo Rivoira, Marta Tagliani, Caterina Saracco, Alessandra Tomaselli, Ruth Videsott, Alessandro Vietti & Barbara Vogt., Zenodo (Link).

- Tomaselli et al. 2022 = Tomaselli, Alessandra / Kruijt, Anne / Alber, Birgit / Bidese, Ermenegildo / Casalicchio, Jan / Cordin, Patrizia / Kokkelmans, Joachim / Padovan, Andrea / Rabanus, Stefan / Zuin, Francesco (2022): AThEME Verona-Trento Corpus, Eurac Research CLARIN Centre (Link).

- Tomaselli/Bidese 2023 = Tomaselli, Alessandra / Bidese, Ermenegildo (2023): Fortune and Decay of Lexical Expletives in Germanic and Romance along the Adige River, in: Languages, vol. 8, 1, 44 [Number: 1 Publisher: Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute] (Link).